If I had been a diviner – capable of foreseeing the future, perhaps I would’ve appreciated some of my young life experiences much more fully. Perhaps. But back then, I was just a wide-eyed teen-ager – a first-year university student living in the big city for the first time, away from my family, and more than ready to enjoy my newly-found freedom.

If I had been a diviner – capable of foreseeing the future, perhaps I would’ve appreciated some of my young life experiences much more fully. Perhaps. But back then, I was just a wide-eyed teen-ager – a first-year university student living in the big city for the first time, away from my family, and more than ready to enjoy my newly-found freedom.

Part of that freedom involved late weekend nights at the Peña de los Parra, which, I learned much later, had been at the centre of the budding 1960s New Song Movement in Chile and Latin America. This continental phenomenon was offering innovative renditions of indigenous and traditional folk music while infusing it with lyrics of protest and vision, incorporating indigenous instruments into their compositions, and aiming at blurring geo-political borders in favour of a continental identity.

If I had realized then that I was witnessing the emergence of a whole new way of making music and that the Peña was playing a significant role in its development, would I have been more attentive, more appreciative, and more inquisitive? For example, the evening that a twenty-something Víctor Jara got onto the small stage, sang El cigarrito and then joined my friends and me for an empanada and a glass of wine, why didn’t I ask him about his collaboration with legendary Violeta Parra?

Isabel and Ángel Parra, Violeta’s children, had established their peña in 1965 in an unassuming adobe house on Calle Carmen, in Barrio San Isidro, one of Santiago’s oldest neighbourhoods. Accomplished musicians themselves, Isabel and Ángel performed their own compositions as well as Violeta’s, plus other Latin American tunes little known to Chileans until then.

During those years, singer, composer, researcher and visual artist Violeta Parra was scorned by the mainstream as a simple country woman with delusional artistic pretensions. Not that Violeta cared – she just carried on with her work, her long, unstylish hair and naked face; her plain clothes, her unembellished self. She carried on, indifferent to the foreign music that filled the radio waves and to what passed for “traditional” folklore – repetitive tunes with hollow lyrics generated by land-owning men in praise of the beautiful land their ancestors had stolen from aboriginal people and of women with thick braids and flowery dresses who waited for them patiently (and with their legs crossed), under weeping willow trees.

While many of us enjoyed The Beatles, Nicola di Bari and Charles Aznavour, we hated the landowners’ folklore and admired Violeta and her work. As an ethnomusicologist – a term she would not have used herself but that actually describes aptly one of her endeavours, she was uncovering the beauty and wisdom of popular musical forms and world views previously unknown or considered to be “ignorant” and “low class.” The young musicians that we listened to at the Peña de los Parra appreciated this better than anyone else and not only performed their own renditions of Violeta’s work but also followed in her footsteps when creating their compositions.

When I started going to the Peña, Violeta was in Bolivia. She had followed Run-Run there – a Swiss musician twenty years her junior, with whom she had fallen madly in love. But Run-Run’s admiration for her had turned into indifference, and Violeta came back to Santiago penniless and with a broken heart. This unrequited love served as the basis for some of her last compositions, such as Volver a los Diecisiete – “To Be Seventeen Again,” and Gracias a la vida – “Thanks to Life” which, for many, are her most profound and beautiful creations.

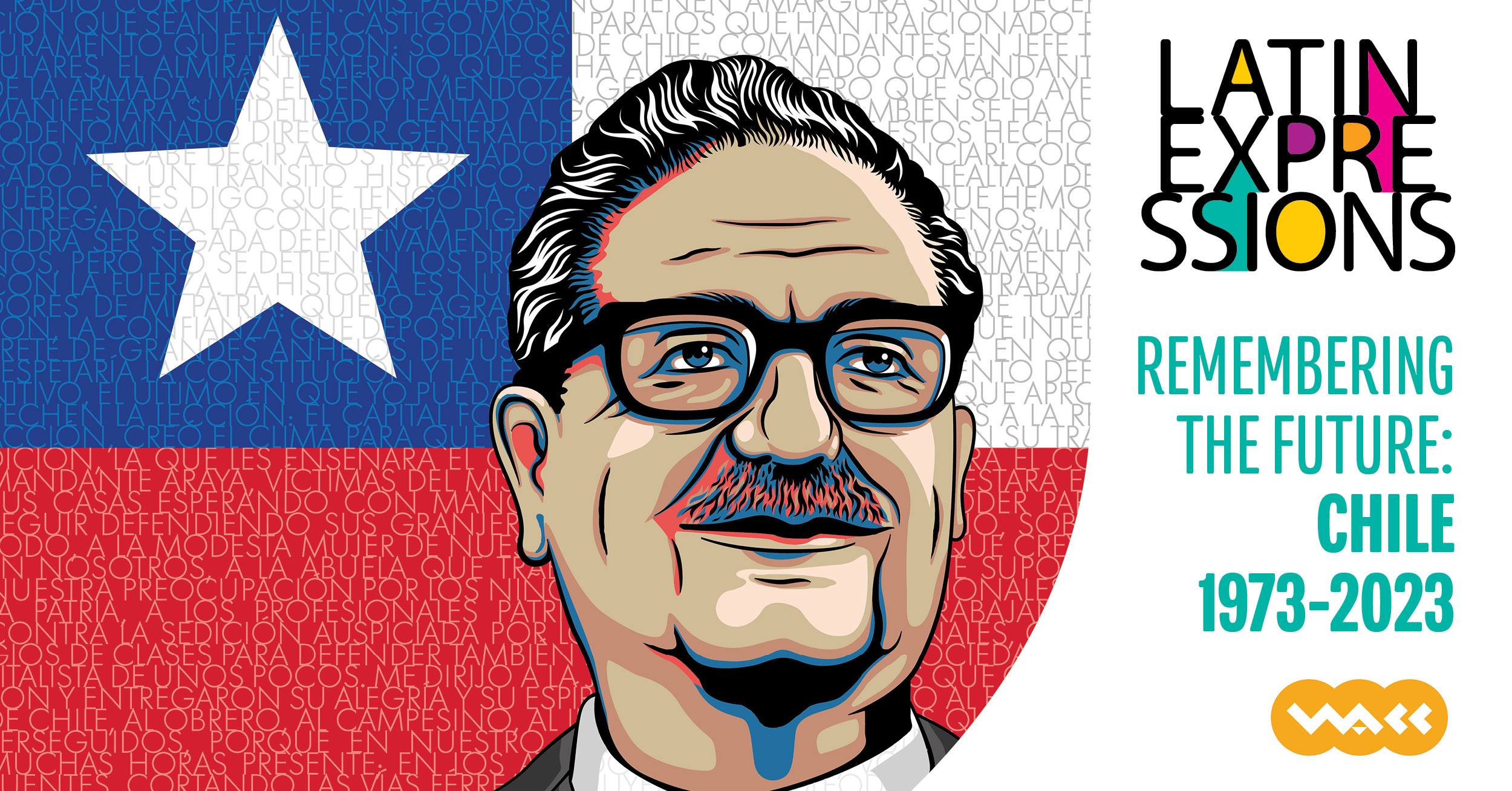

When Violeta Parra took her own life in 1967 at the age of fifty, most likely, she had no idea of the impact that her work was already having and would continue to have on Latin American musicians. She didn’t know that a few years later, she would be considered the “Mother” of the New Song Movement. Similarly, like the rest of us, Violeta would’ve hoped but not predicted that three years later, Salvador Allende would become President of Chile; nor would she have suspected that on September 11, 1973, Allende would be assassinated in a violent coup d’etat, her friend and mentee Víctor Jara would also be killed, and her son Ángel would end up spending months in a concentration camp, followed by years of exile, together with her daughter Isabel.

This October 15, we will be honouring Violeta and New Song giants such as Víctor Jara, Quilapayún and Inti-Illimani, as well as more contemporary Latin American singer/songwriters like Julio Numhauser, Joe Vasconcellos and Natalia Lafourcade at REMEMBERING THE FUTURE, an inspiring and momentous event at Vancouver’s Orpheum Theatre. The evening will combine their music with poetry by Pablo Neruda, Gabriela Mistral and Nicolás Guillén, among others, and photography and art by Brigada Ramona Parra, Nemesio Antúnez, Eva Lewituz and Gracia Barros, to name a few; all in commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the military coup in Chile and in celebration of the arrival of Chileans and all Latin Americans in Vancouver.

See you there!

REMEMBERING THE FUTURE – CHILE 1973-2023

SUNDAY, OCTOBER 15 – 7:30 pm

ORPHEUM THEATRE

601 Smithe Street

Vancouver

Carmen Rodríguez

© Carmen Rodríguez, 2023